Supreme Court

JACK POPE

A COMMON-LAW JUDGE

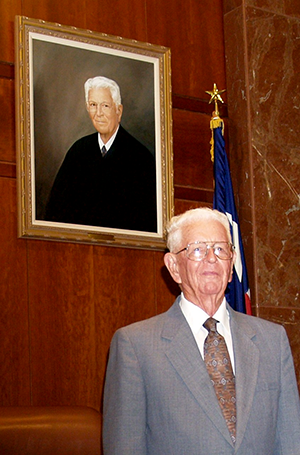

Chief Justice Pope served Texas for 38 years as a district court judge, court of appeals justice and on the Supreme Court, the last two as chief. His judicial tenure as a whole was the longest of any Texas Supreme Court justice.

As a court of appeals justice, Pope’s reassessment of water rights conveyed by Spanish and Mexican land grants changed Texas water law forever. As chief justice he forged a way to guarantee income to finance legal assistance for the poor. Concerned with double litigation in the same case, he won legislative support for statutory changes to thwart “forum shopping” for favorable judges.

“I’m a common-law lawyer,” he proudly would proclaim, his right hand jabbing at the air to his side, his voice emphatic in the way Jack Pope’s can get emphatic when his passions run high about the law and judging. “And I was a common-law judge.”

The common law is the wisdom of the ages, he believes, but for him it was more than that. “This is history and it’s why the poor man, or the black man, is treated the same as all others,” he said.

By the time he retired in 1985, he wrote 1,032 opinions – a record in Texas, by his reckoning. Two of them were considered among the most-important opinions in the state’s history.

“Common-law opinions,” he once said, proudly.

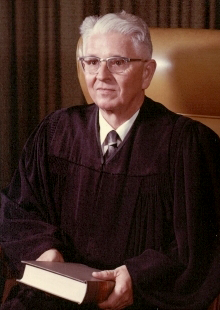

With his chiseled features and shock of white hair, Hollywood could not have cast a better judge.

His wife of 66 years, Allene Nichols Pope, died in 2004. On the back of her headstone at the Texas State Cemetery he had inscribed: “Allene is the difference between deeds and wishes, finishing and quitting, success and failure.”

One of his law clerks, former state Rep. Dan Branch of Highland Park, used the analogy of the old Olympics figure-skating scoring method to congeal the Pope legend. “Whether judging him as a man or a jurist or legal scholar or writer,” Branch said, “whatever aspect of his life, I’d hold a 10 up.”

“Judge Pope was such a legend in the law, such a respected jurist,” said another law clerk, Gwendolyn M. Bookman, director of Bennett College’s Center for Global Studies in North Carolina, who believes she was the first African-American woman to clerk for the Court. “Certainly working for and with him was the greatest honor of my career.”

The sweep of his reforms and his opinions changed Texas law forever, said Austin attorney Steve McConnico, a former law clerk. “What he did for trial practitioners, there’s no way to measure it.”

“He really studied the law. If Roscoe Pound wrote something, he read it. If Cardozo wrote something, he read it.”

Senior U.S. Circuit Judge Thomas Reavley, a former Texas Supreme Court justice, did not hesitate to name the best jurist among hundreds with whom he served in a judicial career extending almost 60 years, including judges on all but one of the 11 federal regional circuits.

“Jack Pope,” he said.

Andrew Jackson Pope was born to Dr. A.J. and Ruth Pope in Abilene in 1913, the year Henry Ford revolutionized automobile manufacturing with the assembly line and the year road-builders completed the first coast-to-coast paved highway.

Pope graduated in 1934 from what was then Abilene Christian College. In a sense, he never left his hometown, serving for years as a trustee on the Abilene Christian University board.

He earned his law degree from the University of Texas three years later and began law practice in Corpus Christi under an uncle’s tutelage. The library table that was his first desk in his uncle’s office sits as the centerpiece of his Austin study.

On one corner rests the standup Royal typewriter Pope used to collect and express his thoughts, and, in his retirement, his memoirs, a family history and a tribute he published to honor a coterie of dedicated care-givers he depended on.

Following a stint in the Navy in World War II, Pope took his first bench in Corpus Christi in 1946, on the 94th District Court, and served for four years.

In 1951 he left for the San Antonio Court of Appeals, having beaten three contenders without a runoff in the all-important Democratic primary, becoming the first justice on the court from south of San Antonio. He served on that court for 14 years until his election to the Supreme Court of Texas in 1964.

A lifelong Democrat, he won his seat on the Court also in a three-way primary without a runoff when Texas was essentially a one-party state. He never had opposition for re-election to the court of appeals or Supreme Court.

But his appointment as chief justice to succeed Joe Greenhill might have been his greatest political triumph. By his recollection, Gov. Bill Clements, the first Republican governor since Reconstruction and a lame duck defeated in late 1982, could not find a chief justice who would survive the blackballing by which senators could kill an objectionable appointment from their home districts.

Greenhill urged Clements to appoint Pope. But 14 Democratic senators pledged to block any appointment Clements made, essentially dooming it in the Senate. They argued that such an important appointment should be saved for incoming Gov. Mark White, the Democrat who beat Clements.

White gave unqualified support to Pope.

So Clements picked Pope, who had voted for White. Despite the opposition, Pope took the oath, then demanded that he get the prerogative of giving the State of the Judiciary speech.

In his speech Pope argued for reforms he had championed for years. He urged nonpartisan judicial elections and, to promote equal access to justice for the poor, approval of the so-called IOLTA program to pay for civil legal help for the poor with interest on lawyers’ common client-trust accounts. He argued for overhaul of what he considered Texas’ wasteful venue statutes that almost guaranteed two trials – one on the venue question and one on the merits.

In a chapter for his memoirs he described resisting offers for a deal to win the Senate’s approval. Pope had no plans to run for the chief justice position because he would turn 75, the mandatory retirement age for Texas judges, in the middle of another term. But he said senators wanted him to promise to resign after the Senate approved him to allow White’s appointee as chief justice to run as an incumbent in the next election.

Pope said no. Such a deal would be unethical, even illegal, he said. “If the public sees that I will make a deal to get a job and to keep a job,” he later wrote, “then maybe they’ll think I’ll make deals on other matters.”

Branch chuckled at the thought. “How could you complain about Jack Pope? It was brilliance by Clements. He picked someone who was unassailable.”

Pope’s force for judicial education began as soon as he donned his robe in Nueces County. As a new judge he set a goal.

“At that point,” he recalled, “I decided I was going to read legal literature, one chapter every night, seven nights a week, for 12 to 15 years.”

Years later, many of those books and more line the shelves of his home library in Austin. Talking about his life, Jack Pope pulled a book from a section of library, a copy of Minimum Standards of Judicial Administration.

“This is my Bible,” he said.

It could have been instead one of four volumes of Jurisprudence by the great legal scholar Roscoe Pound or a copy of the Magna Carta story or one of three volumes of Law and Society. Or any of the others among hundreds of books packed floor to ceiling with biographies and treatises in a library the size of a double-car garage.

“These,” he said of the books lining his walls, “are my friends.”

When he was on the appeals court, he wrote New York University Law School to ask whether it offered judicial education for intermediate-appellate judges. NYU had the only judicial-education program in the country, but limited it to state supreme court jurists.

Finding nothing, he worked for years for judicial education, assisted in founding the Texas Center for the Judiciary, a judicial-education institute, and signed the order mandating education for Texas judges.

But judicial education was only one of several judicial-administrative reforms he envisioned. In 1962, when he was on the appeals court, a State Bar committee he chaired drafted the first voluntary judicial-ethics code. In 1972, when he was on the Supreme Court, he drafted the first mandatory judicial conduct code for Texas judges.

Perhaps his greatest contribution to Texas law, however, was State v. Valmont Plantations, decided in 1961 while he was on the San Antonio Court of Appeals. In Valmont, Pope reevaluated a landmark water-rights case from three and a half decades before, found it laden with dicta and without analysis of Mexican and Spanish land grants even though those land grants should have been critical to the decision.

So Pope cast aside the notion that he was abandoning settled law, methodically demonstrating its fallacies. His Valmont decision was a proud legacy because the Texas Supreme Court adopted his opinion as its own, a rare move.

Valmont reassessed water rights conveyed by Spanish and Mexican land grants. It held, in a case by landowners along the Rio Grande suing for irrigation water from the new Falcon Reservoir on the Texas-Mexico border, that irrigation-water rights in the Lower Rio Grande Valley were not included in Mexican and Spanish land grants unless expressly mentioned in the grants.

When historical novelist James Michener researched water and its bearing on Texas history for his novel Texas, Branch recalled, Michener called on Pope to explain it.

“His researchers had figured out that he was water law,” Branch said.

In 1986, University of Texas law Professor Hans Baade honored Chief Justice Pope after his retirement with a law-review article titled, “The Historical Background of Texas Water Law – A Tribute to Jack Pope.”

Abilene Christian, Pepperdine, Oklahoma Christian and St. Mary’s universities awarded him honorary degrees.

In 2009 the Texas Center for Ethics and Professionalism presented its first Jack Pope Professionalism Award to Pope. In 2010 the State Bar’s Judicial Section honored him with a lifetime achievement award.

“Just about the time I was getting the hang of being a judge,” he said once, “I had to retire.”

In a quarter-century of retirement he keeps active, studying and writing about the law and his family history, preparing books and papers for donation.

His is a familiar figure as he walks through his West Austin neighborhood in the hills that climb above Tom Miller Dam.

At 96, determined to walk 9.6 miles for his birthday, an Austin television station featured him preparing by stretching lengthwise across his legs to touch his toes. High school athletes would have been envious.